-

Collaboration

Top 10 Team Management Software to Boost Collaboration in 2025

-

Internal Comms

Business Email Etiquette 101: Examples of Do’s and Don’ts

-

Employee Engagement

Workplace Professionalism: What It Is and Why It Matters

-

Employee Engagement

Employee Advocacy: Definition, Benefits, and How to Leverage

-

Internal Comms

What is Business Communication? 10+ Examples

-

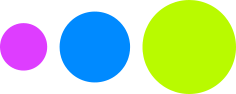

Intranets

Intranet Market Size: Trends, Growth, and the Road Ahead in the Global Intranet Software Market

-

Employee Engagement

Toxic Work Culture: Causes, Symptoms, and How to Cure for Good

-

Employee Engagement

Employee happiness: How to keep employees happy (No, pizza parties won’t cut it)

-

Collaboration

What Are Action Items? (With Examples and Practical Templates)

-

Internal Comms

What is External Communication? Definition, Benefits, and Best Practices

-

Employee Engagement

Employee Disengagement: Why Employees Drift and How We Can Fix It

-

Internal Comms

What Is a Communication Gap in the Workplace and How to Bridge Them

-

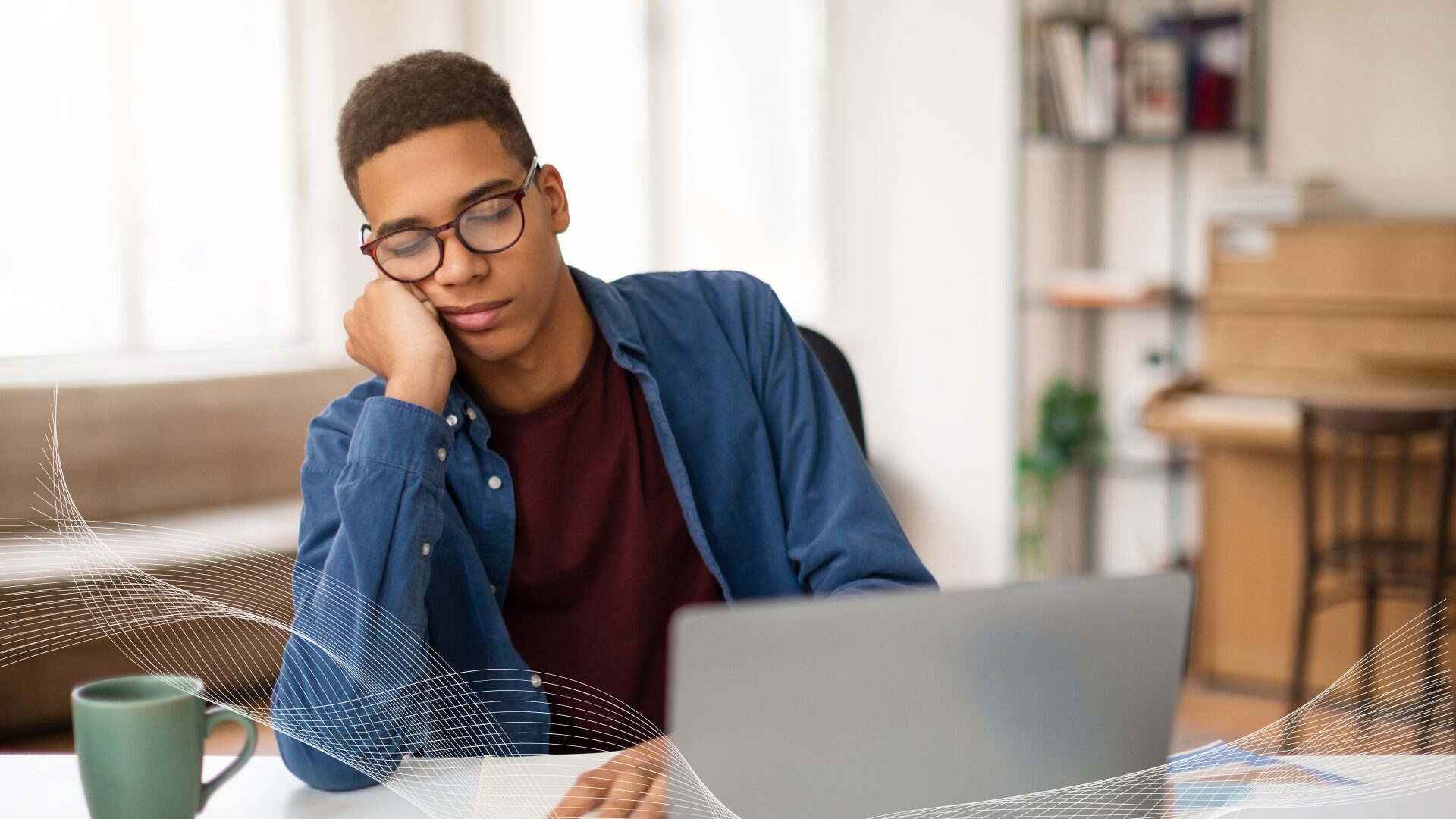

Knowledge Management

Knowledge Management Benefits: 9 Ways To Streamline Your Workplace

-

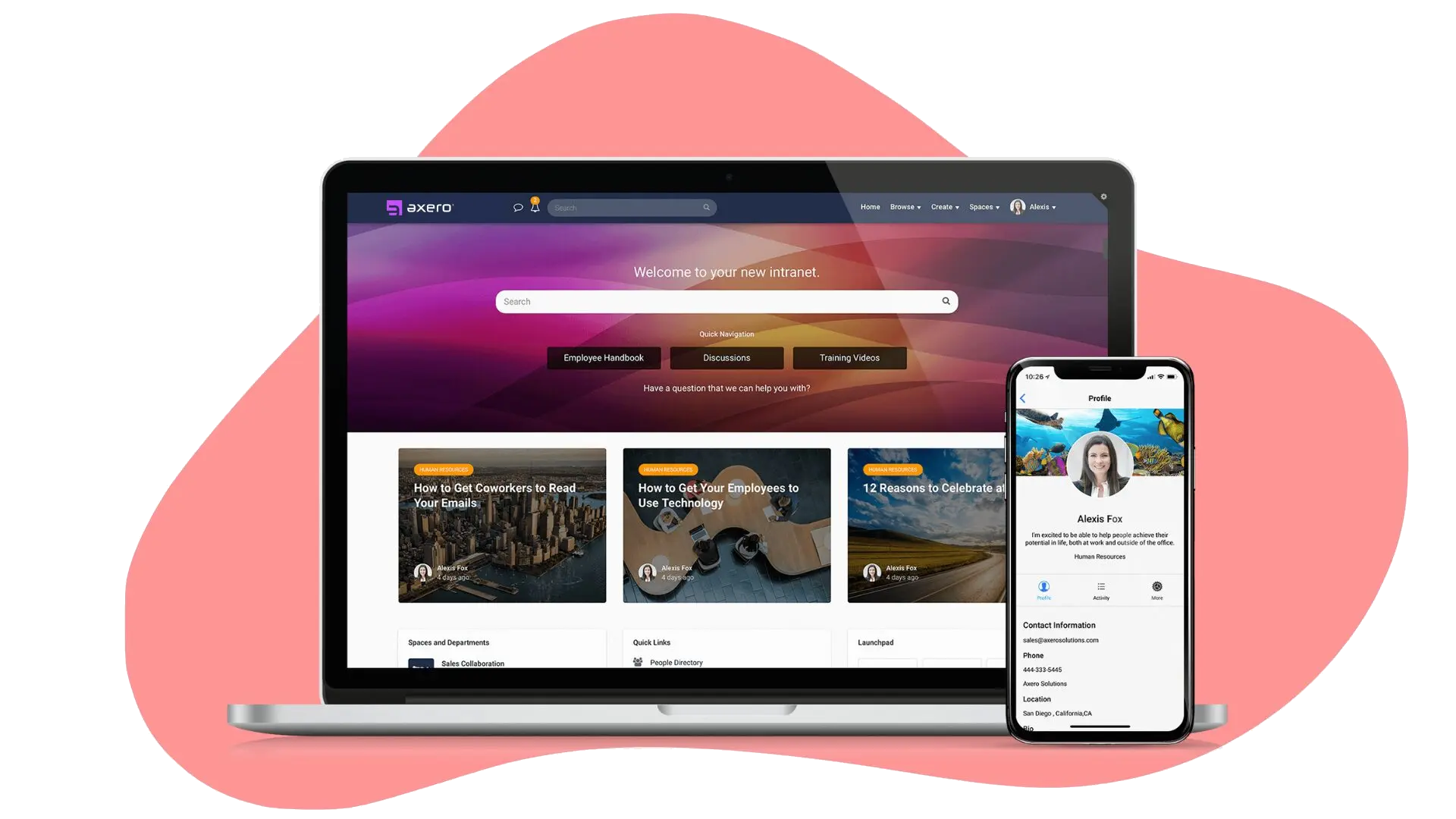

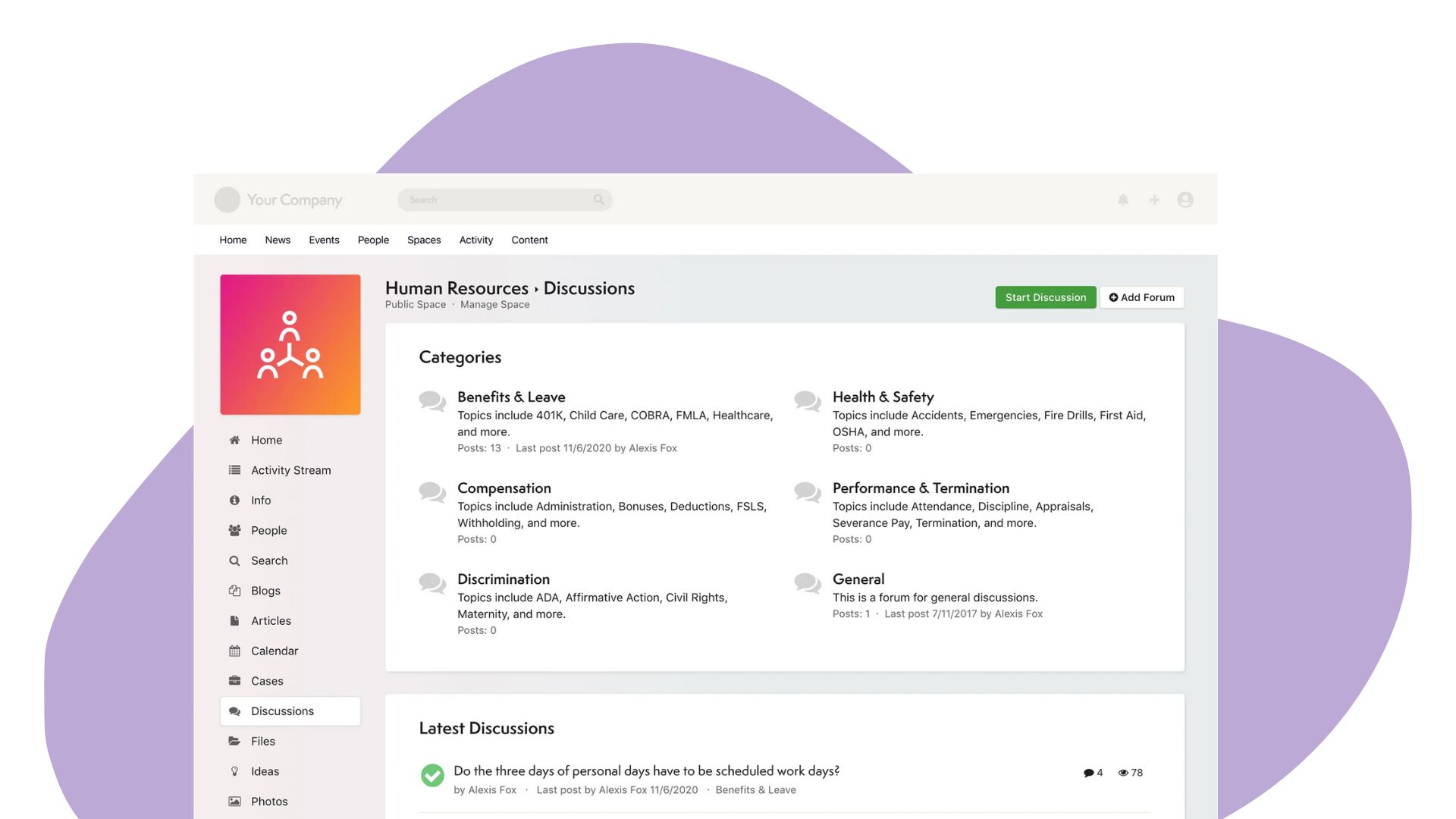

Intranets

Top 11 Best Intranet Software Platforms of 2025

-

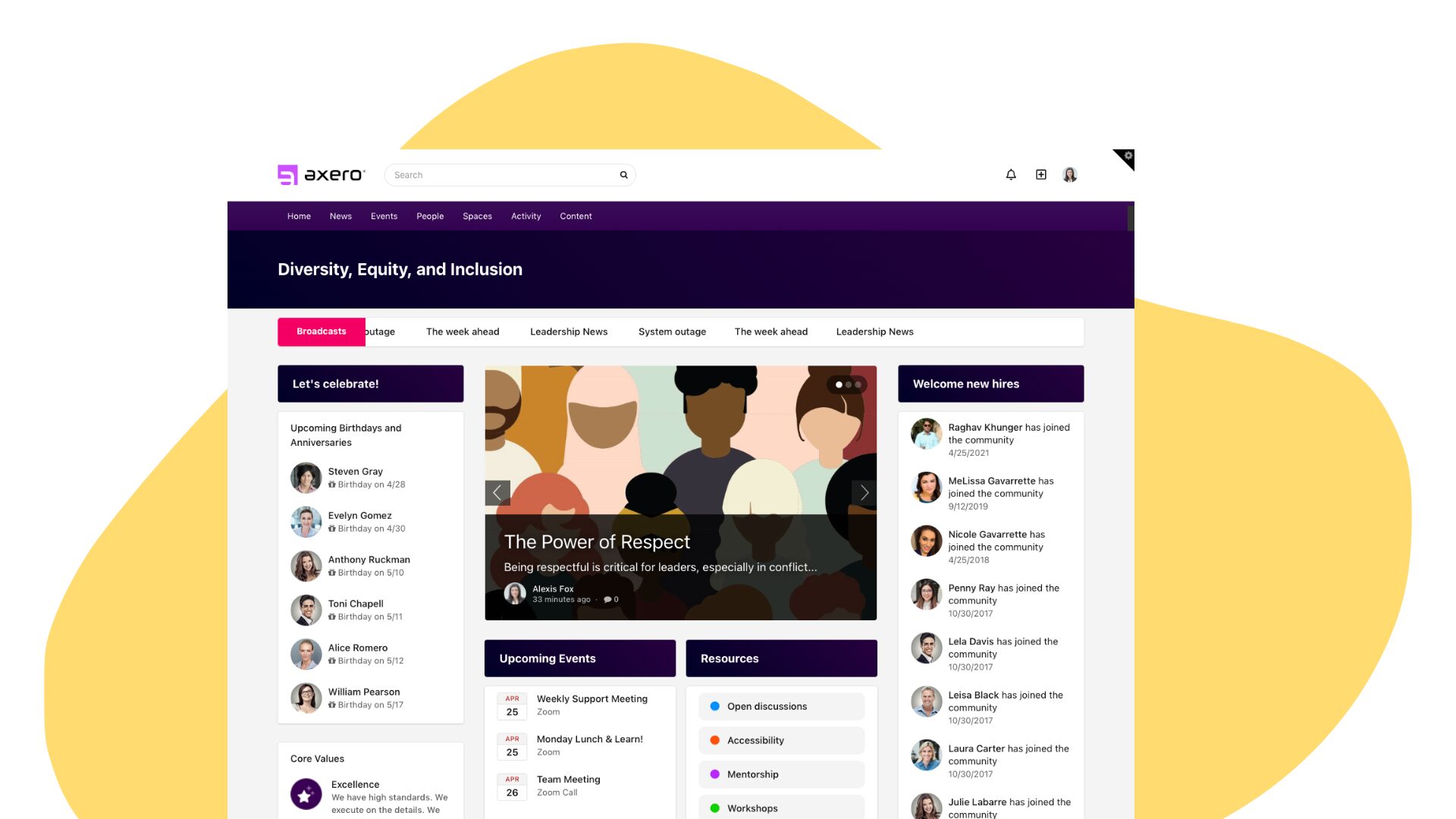

Advice

DEI Examples: Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Initiatives in Action

-

Advice

13 Best HR Conferences to Attend in 2025

-

Employee Engagement

70+ Positive Affirmations For Work

-

Employee Engagement

20+ Self-appraisal Comments By Employee Example: What You Should Think About for Your Development

-

Employee Engagement

7 Intranet Content Ideas That Will Actually Boost Employee Engagement

-

Advice

HR Full Form & The Ultimate Guide to Human Resources

-

Knowledge Management

12 Best Knowledge Management Software in 2025

-

Employee Engagement

20 Best Employee Experience Software for Companies in 2025

-

Employee Engagement

16 Best Company Culture Software in 2025

-

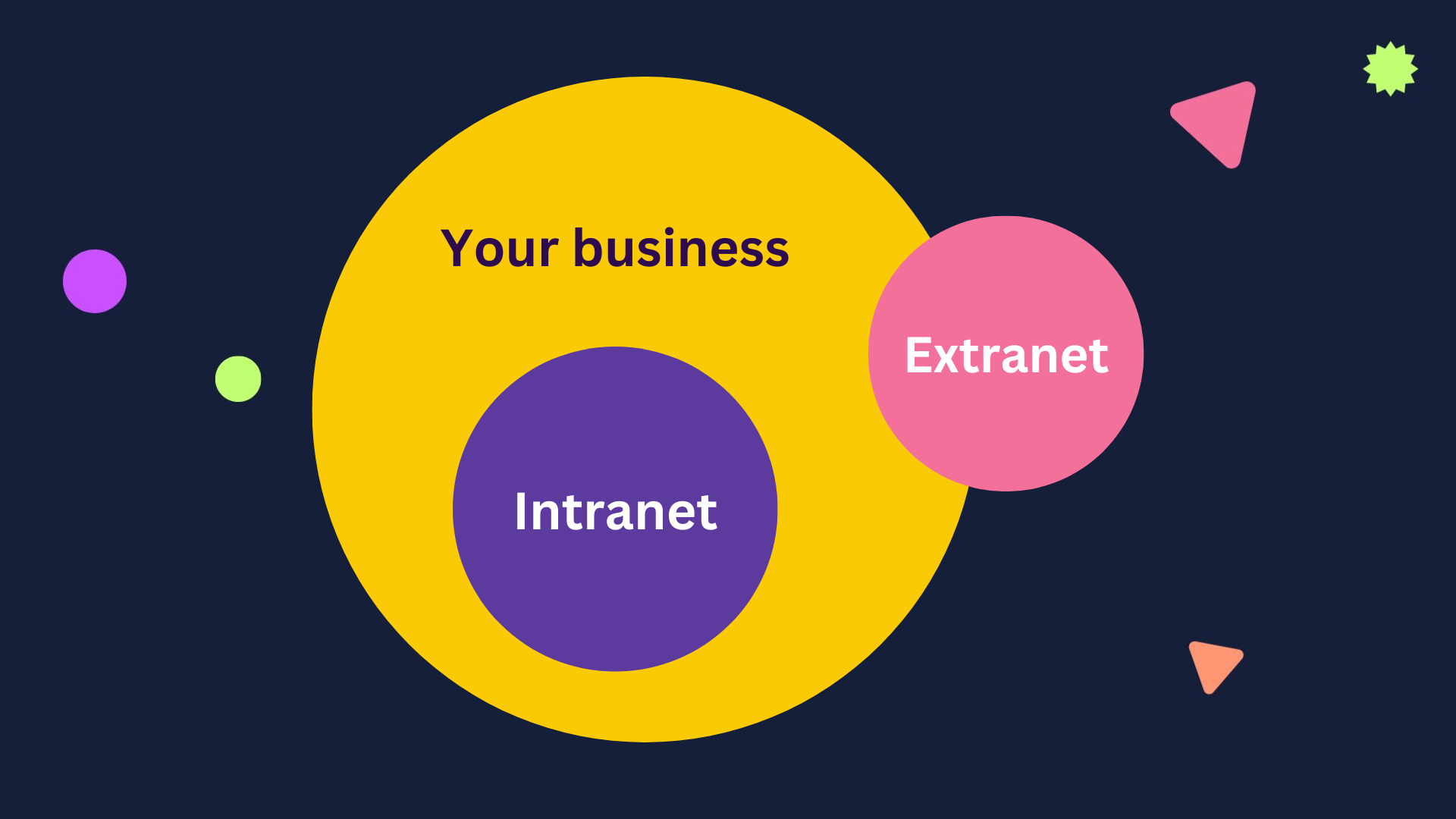

Intranets

Intranet VS Extranet: What’s the difference?

-

Employee Engagement

Employee Engagement Strategies: Best Practices for 2025 and Beyond

-

Intranets

14 Best Cloud Intranet Software Solutions

-

Internal Comms

13 Best Internal Communication Software for Business in 2025

-

Knowledge Management

What Is a Knowledge Management System and How It Fits Into Your Business

-

Internal Comms

Too Many Emails at Work? Here’s How to Manage Email Overload

-

Employee Engagement

What Is Employee Branding? Creating In-House Ambassadors for Your Business

-

Employee Engagement

What Are Company Values? Why You Need Them, and Examples to Embrace

-

Employee Engagement

What is Positive Feedback? 30 Positive Feedback Examples We All Need To Use

-

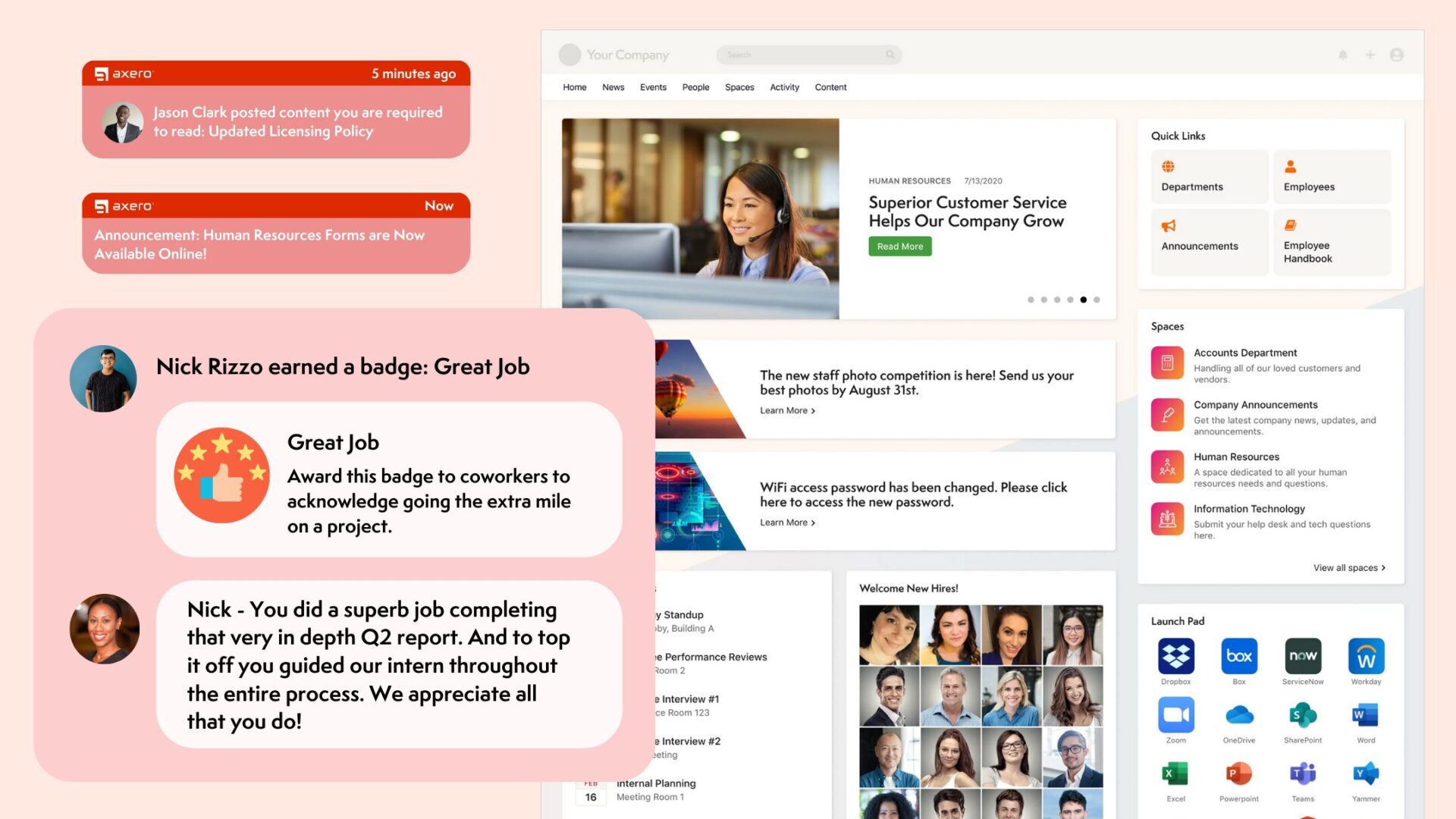

Employee Engagement

What Is Employee Recognition and Why It’s More Than a Job Well Done

-

Internal Comms

12 Ways Business Communication Tools Strengthens the Workplace

-

Employee Engagement

Destructive Criticism 101: Why Tearing Things Down Never Builds Employees Up

-

Employee Engagement

What Does Autonomy at Work Really Look Like?

-

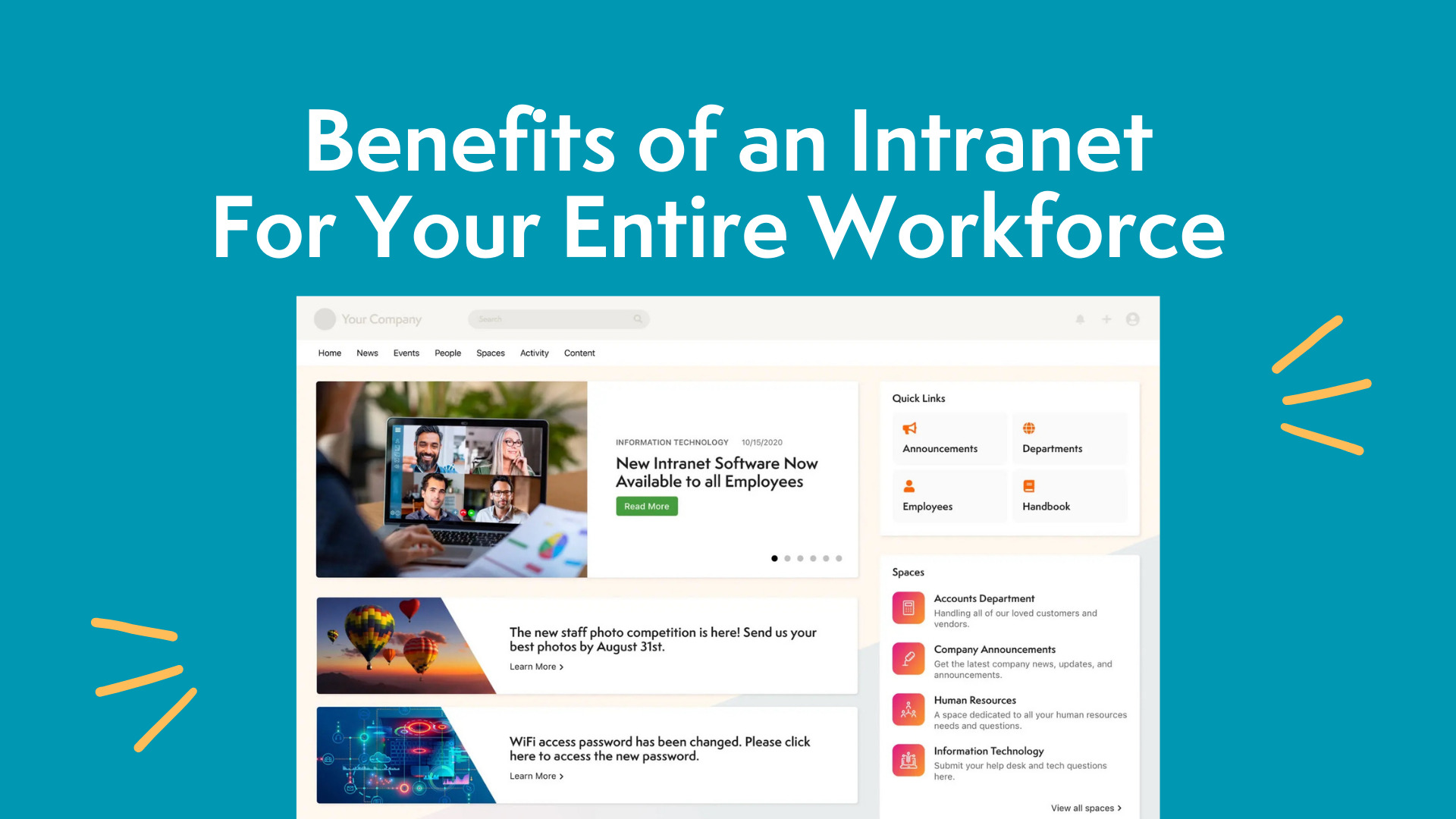

Intranets

31 Benefits of an Intranet for Your Entire Workforce

-

Employee Engagement

What is Employee Productivity and How Can You Boost It?

-

Employee Engagement

20+ Employee of the Month Ideas

-

Intranets

How Can a CMS Employee Intranet Help Your Company?

-

Internal Comms

What Internal Communications Is and Can Be In 2025

-

Knowledge Management

Corporate Wiki vs Knowledge Base: Which Is Better in 2025?

-

Intranets

What is a Virtual Workspace? Key Considerations for Hybrid and Remote Teams

-

Employee Engagement

30 Best Employee Engagement Tools in 2025

-

Intranets

What Is a Digital Workplace?

-

Internal Comms

Corporate Communications: What Is It and Why Is It Important?

-

Employee Engagement

How Employee Experience Helps You Build a Better Workforce

-

Employee Engagement

Bad Leadership: How to Spot It, and How to Be Better

-

Internal Comms

Lack of Communication in the Workplace: What It Means and How to Fix It

-

Collaboration

What is Enterprise Social Networking?

-

Intranets

How to Break Down Business Silos

-

Employee Engagement

10 Constructive Feedback Examples That We Should All Try to Use More

-

Intranets

Intranet ROI: 10 Tips to Consider When Attempting to Measure It

-

Employee Engagement

The Psychology of Gamification in the Workplace

Collaboration

Collaboration Internal Comms

Internal Comms Employee Engagement

Employee Engagement