The weekend before Monday, August 21, 2017, these signs were up all over town, not just here in San Diego but all over the U.S.

For the first time since 1979, a total solar eclipse, visible across the continental U.S., was going to happen, and people scrambled for the special glasses that would allow them to see it without damaging their eyes. You can imagine what happened when the glasses weren’t available anymore. Stores that still carried them had hours-long lines, and fights broke out over the remaining pairs. People even started making and selling fake eclipse glasses, which was especially scary. The eclipse glasses were a hot commodity, and the scarcer they got, the more people talked about them. In the days leading up to the solar eclipse that Monday, their scarcity became an hourly news story. The eclipse was neat. A total solar eclipse is a rare event, but the glasses were the hot story. Why? The principle of scarcity was at work.

My post Persuasion at Work touched on this principle. Robert Cialdini wrote at length on the topic in his two books Influence and Pre-Suasion. You can use scarcity as a manager to improve the lives of your employees at work.

Scarcity Recap

Scarcity may be the most difficult persuasion principle to understand when it comes to its function in the workplace; but let me reassure you that when applied with care, it does have a positive and powerful role in workplace dynamics. Watch almost any animal show on the Discovery Channel and you’ll see scarcity in action. Scarce resources increase competition, and competition, in turn, increases desire. Whether the animals are putting on intricate displays to attract mates or fighting over the last scrap of food, if there is less of something, the animals want it more and are willing to work harder to get it.

We’re animals too, remember. Psychologists refer to the oldest, most primitive part of the human brain as the “lizard brain.” It’s instinctive, in charge of fight, flight, fear, freezing up (fear paralysis) and reproduction. As thinking, feeling human beings, we might think this part of ourselves is buried, smothered by our more advanced cognitive abilities, but we’d be wrong. When the lizard brain gets triggered, it causes us to do things without conscious thought.

Scarcity triggers our lizard brains like little else does. It makes us want what we can’t have. It’s a powerful psychological force. In the workplace, if you take control of its power, you can help your employees get more done, work better together and feel happier on the job.

Scarcity Element 1: FoMO

FoMO is not something just the cool kids are texting these days. It’s a real, psychological phenomenon that’s been aggravated by social media, and it has everything to do with scarcity. FoMO stands for “Fear of Missing Out.” A recent ScienceDirect study defines it as, ”The uneasy and sometimes all-consuming feeling that you’re missing out—that your peers are doing, in the know about, or in possession of more or something better than you.” It’s that feeling you get when you choose not to attend a party but see Instagram pictures of your friends at the party while you’re in your pj’s on the couch at home. It’s the gut-wrenching sensation you get when you see a college friend posting messages from a Caribbean island while you’re in your cubicle at work, or the urge you feel to find out more about an event everyone’s talking about online. It’s a bit of jealousy, a dash of social proof, and a whole lot of, “Am I missing out on something that I’ll never get the chance to do, have, or see ever again?” FoMO is the result of your lizard brain sensing scarcity.

In the workplace, you can turn this to your advantage when encouraging your employees to take advantage of opportunities. When training employees, frame the training as something that won’t come around again soon. Let your employees know that X number of their peers have already signed up, too. FoMO just may kick in and your team may change its perspective. Training becomes less of a burden and more of a unique opportunity on which members may regret missing out. This “loss framing” can be just as valuable as FoMO.

Scarcity Element 2: Loss Framing

How you frame messages to your employees has a direct effect on how the message is received. Whether you’re trying to persuade them to do something or to stop doing something, consider whether you’re framing the change in behavior as a gain or a loss. In other words, are you focusing on the positive, or are you focusing on cost or risk?

“Gain framing” means you’re focused on communicating the positive benefits. “Loss framing” means you’re focused on communicating the loss—minor or otherwise. A gain-framed message could be, “You’ll live longer if you stop drinking alcohol.” The loss-framed version would be, “You’ll die sooner if you do not stop drinking alcohol.”

Study after study has shown that we human beings do more to avoid pain than we do to seek gain. We’re more sensitive to loss—even minor loss—than we are to gain, especially if the outcome is more uncertain.

Not sold? Try these two statements on for size:

- Do three jumping jacks, and I’ll buy your lunch for the next two days.

- Don’t do three jumping jacks, and you’ll have to pay for my lunch tomorrow.

Which one feels more compelling to you? Probably, number two is.

You see loss-framing in every marketplace. Businesses use many different forms of it to trigger the feeling of scarcity in us: “If we don’t do this, we’ll lose out!”

- Coupons with expiration dates that aren’t that far away.

- A vendor letting you know the prices are going to go up on a particular product next week.

- Ads that say things like, “If you don’t put new windows on your house, you’re losing $30 a month in air conditioning or heat loss.”

A study described in both this Science article and Dean Buonamano’s book Brain Bugs: How the Brain’s Flaws Shape Our Lives shows us how powerful loss framing really is. First, participants were given $50. They were asked to make a choice between keeping $30 or gambling the money with a 50/50 chance of keeping or losing the whole $50. The majority of the participants chose to keep the $30. Then the researchers switched things up. Participants were asked to choose between losing $20 or gambling the money with a 50/50 chance of keeping or losing the whole $50. With the situation framed as a loss, the majority of the participants chose to gamble!

Simply framing the situation as a loss changes human behavior.

I use this concept to help guide our new Axero customers in onboarding their employees, and I’m sure you can find a way to use this in your own workplace as well. Here’s how I do it: I tell my new customers to put all of their important company resources on the intranet. Benefits brochures, handbooks, policies, procedures, contact lists – everything for which employees typically go to HR or their managers, put it on the intranet. Then, take all of those assets down from everywhere else. Remove it from cloud drives and shared folders. Pull hard copies out of the file drawers. Let HR and any team leads know that they shouldn’t even email these assets to employees. If an employee needs information, he is to be directed to the company intranet.

After that, the intranet should be the one and only place employees can get critical information about their jobs and their benefits. Finally, use loss framing to communicate to employees: “You are losing access to this material everywhere but on the company intranet.” Believe it or not, this dramatically increases intranet uptake and usage within our customers’ organizations.

Scarcity Element 3: Time-based Scarcity

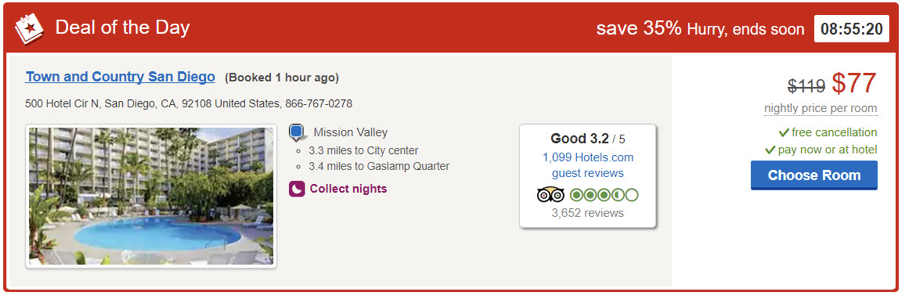

Loss framing isn’t the only way to create scarcity, though. When you think of scarcity, time-based scarcity is probably the first thing that comes to mind. Every ad you see on TV, in the newspaper or online seems to use this tactic to get you to, “Act now! This deal ends soon!” Marketing has many great examples:

- Daily deals (think Amazon.com).

- Limited-time offers.

- Clearance sales (think end-of-the-year inventory clearance sales on furniture and cars).

- Holiday specials (think Starbucks and their Pumpkin Spice Latte).

- Once-in-a-lifetime offers, one-of-a-kind specials or unique collaborations (think Beats collaborations).

The fact that once the opportunity is lost, it may not come around again is what makes time-based scarcity work, unless we’re talking about the Pumpkin Spice Latte, of course.

Loss aversion rears its ugly head in the psychology of time-based scarcity tactics. If you don’t take advantage before the deadline, you may lose out … forever. In the workplace, this approach may seem like it’s fear-inducing and inappropriate to use on your employees. However, this method has a time and place.

Consider this scenario: You’re trying to get your employees to fill out paperwork regarding their year-end reviews. About half of your employees have completed the task, but the other half are dragging their feet. You’ve tried being nice; you’ve tried being firm. The answer you keep getting back is, “We’re busy. We’ll do it when we have time.” Meanwhile, your deadline for conducting those reviews is coming up fast.

This might be a great time to use time-based scarcity for the common good. After all, you want your employees to get their reviews because they’re an essential part of their career growth. You could reframe your message from, “Complete this paperwork by X date,” to, “Your opportunity to provide this information and be considered for a salary increase will end on X Date.” Framed like that, your employees are likely to feel more motivated to act before the deadline.

Scarcity Element 4: Rarity and Quantity-based Scarcity

Scarcity can also be created based on rarity and limited quantity. Would you pay $255 for a cupcake? In 2014, one raving fan of Crumbs Bake Shop did just that. Crumbs announced that it would be closing all of its stores, and Likeable Media happened to have one of Crumbs sweet treats in its office refrigerator. The employees agreed that it would be a fun experiment to try to sell it on eBay. Sure enough, one cupcake-craving buyer snatched it up for a little bit more than the opening bid price.

Why in the world would someone pay $255 for a two-week-old cupcake? Its rarity drove the price. Crumbs cupcakes were no longer available, so some people’s desire for them skyrocketed.

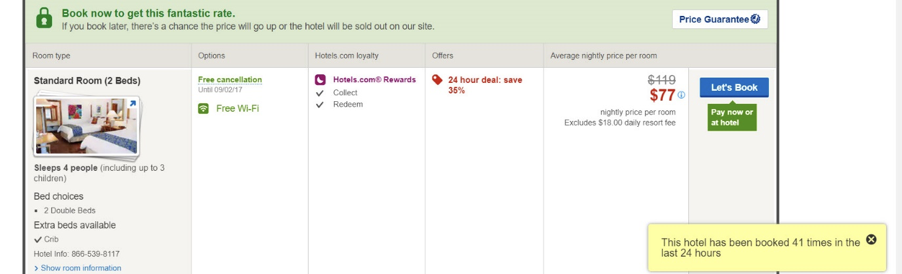

Like time-based scarcity, loss aversion plays heavily into quantity-based scarcity. When less of something exists to go around, desire for it increases, and the feeling of losing out if you don’t act increases. Hotel and travel websites use this to motivate customers to make a purchase. Pull up almost any hotel booking site and you’ll see bold messaging around how few rooms are left for the dates at which you’re looking. Some sites even show how many other people have just booked rooms at that hotel and a special price with a countdown timer next to it to add time-based scarcity. All of this is done in the name of increasing the sense of scarcity.

In Cialdini’s book Influence, he talks about a cookie experiment that illustrates the rarity effect. Some participants were given a jar with 10 cookies in it. Other participants were given a jar with two cookies in it. Then the participants were asked to rate the value of the cookies in the jars. What was the result? The participants who were given fewer cookies rated the cookies higher.

Competition is a huge amplifier of the rarity effect. The scarcer the resource, the more people want it … and the more they’re willing to do to get it. You can use rarity to foster a little good-natured competition in your workplace, too. Try opening just a handful of spots in a training session, and those seats will likely fill fast. Issue limited invitations to an executive lunch, and those lunches will hold much more value to your employees, and you’ll get the benefit of showing off your expert team.

Scarcity Element 5: Exclusivity

Although you may think exclusivity is the same as rarity, it has a slightly different flavor. Just like rarity, though, you can use it to create scarcity. Exclusivity is the reason hot night clubs have block-long lines outside. It’s why airlines can charge exorbitant prices for first-class seats. It’s why people line up an hour before Dominique Ansel’s bakery opens in New York just to get their hands on a simple pastry.

The more exclusive something is thought to be, the more people want it and the more businesses can charge for it. In this way, exclusivity can be either the by-product of limited resources or purposefully manufactured.

Chef Ansel can probably hire a company to mass-produce his special Cronuts® at a fraction of the cost and serve those treats to many more people in the process, but then they wouldn’t be special. They would lose their exclusivity, and likely, they would lose their value as well.

Facebook is so ubiquitous now, but once upon a time, this social media site stood behind a (digital) velvet rope. Mark Zuckerberg rolled out the platform slowly, over time and in a very exclusive fashion. First, in 2004, it was only available to Harvard students. Then, he opened it to other Ivy League students, then high school kids, and then employees at certain companies. Only in 2006 was it made available to the public. By then, the public was champing at the bit to use the new social media site.

A current example of this is Quibb. This news site and forum is strictly invite-only, and founder Sandi MacPherson personally determines who gets one of those coveted invitations. Though she set out to create a professional, online community minus the noise of sites like Reddit and Hacker News, what she ended up creating is an exclusive, online club that founders and executives long to be a part of.

In the office, you can use exclusivity to motivate your employees. If you have only one nice corner office, it’s naturally exclusive, and you can capitalize on that by making it up for grabs once a year. You determine the criteria: highest productivity, most sales, biggest help to the team, most calls logged, most tickets closed, highest customer satisfaction rating, etc. You can use exclusivity in the workplace by creating a team to accomplish a task and limiting the seats on that team.

You can use exclusivity when launching the intranet to your organization, too. Make only a handful of user accounts available, initially, and roll it out slowly, over time (à la Facebook). Every time you release a new batch of available user accounts, your employees will probably feel much more excited to get their hands on their very own.

3 Things to Remember as You Reach the Authority Master Level

Scarcity isn’t all about inducing fear in your employees. It can actually reinforce positive behavior, create increased desire to accomplish tasks, and promote a little healthy competition. You need to remember three things:

- People work harder to avoid loss than to seek gain.

- Scarcity can be organic or manufactured.

- You can compile multiple scarcity elements to increase its effectiveness (e.g., limited supply plus a time limit, or FoMO plus exclusivity).

Congratulations! You have now reached Scarcity Master Level.

In the final installment in the Persuasion Master series, you’ll learn how to use the Unity principle to bring your team together and accomplish more.

info@axerosolutions.com

info@axerosolutions.com 1-855-AXERO-55

1-855-AXERO-55