When it comes to the workplace, constructive criticism is not only needed, but wanted by employees. Feedback enables teams to grow, do better, and exceed future benchmarks. While there’s many tools that help professionals learn new skills to keep improving, constructive feedback is one of the most direct and effective ways to identify areas that need work first.

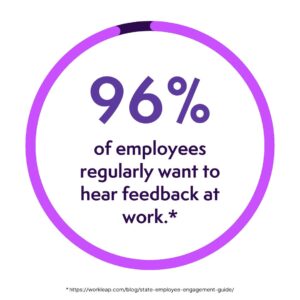

It’s so important to both leaders and team members because constructive feedback keeps employees on track and performing to the best of their abilities. It’s also something that team members want more of. Studies have found that 65% of employees want more feedback—which furthers the point that workers really just want to know how they’re are doing!

Let’s take a closer look at constructive feedback and what it truly means to offer good points intended to support.

What is constructive feedback?

Constructive feedback uplifts and offers guidance to those who need help. The keyword is constructive. It’s crucial to remember that feedback should always be given with empowerment in mind so you can nurture growth and positive change.

When correctly implemented, providing constructive feedback regularly can lead to a positive work environment, stronger levels of employee engagement, and a positive company culture with enhanced collaboration.

The giving and receiving of constructive feedback is an important conversation that should be given the respect that it deserves. Though many constructive feedback examples could indicate how the conversation should run, the truth is that this is a fairly organic process. You could sit down with two people with the intention of delivering the same employee feedback on paper, only to leave the session with two different sets of outcomes.

Constructive feedback vs Criticism

We’ll list some examples of constructive feedback below, but we wanted to take a moment to dive fully into one example to show you the issue at heart and how it should be approached.

Let’s imagine someone tends to enthusiastically speak over others during team meetings. Their ideas are good, but they don’t leave room for others to join the discussion.

Unhelpful criticism might look like this: “You need to stop speaking so much during meetings; no one else can get a word in edgeways.”

Not only does this not offer anything of value, but it’s also impolite. There is nothing in there that will uplift the employee—in fact, quite the opposite. If anything, they will feel ashamed and nervous about presenting in the future. Yes, the employee has learned that they talk too much, but nothing has been offered in terms of support for them or tips to improve, and any self-reflection on their behavior will just be negative. Continuing to deliver negative criticism in this way will not create a feedback culture, and employees could become reluctant to share their opinions.

Constructive feedback might look more like this: “We love your ideas and enthusiasm during meetings, and we have noticed that in sharing your ideas, you sometimes cut off other team members. Can we work together to come up with some ways that you could support their voices?”

This acknowledges that a problem – the overtalking – does exist, but that it isn’t inherently negative, maybe just more misplaced. The feedback addresses the problem but then invites the employee receiving feedback to collaborate with their team to ensure that it doesn’t arise again in the future. This is a much better path and encourages all employees to think about their communication skills at large.

10 constructive feedback examples

Let’s run through some quick-fire examples of constructive feedback. We won’t dive into them as deeply as we did with the example above, but they should be enough for you to think about how to frame some criticism you may be preparing to present to someone.

1. Lack of attention to detail

I noticed that some of your latest assignments aren’t always up to the standards you hold yourself to. Is there an issue I can help you with?

2. Poor deadline management

Across the last quarter, I noticed that you have moved your deadlines around a lot, and you have had to push to get a few projects across the line. Can we set up a meeting to discuss your workload and how we can help you out?

3. Poor attitude

Hey, the team has noticed that your mood seems to be down these days and we are all concerned for your well-being. Is there anything we can do to help?

4. Absent employee

I was expecting you to join us at the meeting – we missed your input! Did something come up that you need help with instead?

5. Employee has gaps in their skills

We would love to see you take ownership of this task more confidently. Would you be open to training and development in this area to support you further?

6. Lack of collaboration

While we love to hear your solutions, we only see you share them with management and not the wider team. Is there anything we can do to help you feel more at ease with sharing and working with everyone?

7. Lack of communication

It is great to see you get so involved with your tasks, but it seems like you often dive in too deep without letting others know what you are doing. Colleagues working on projects with you can sometimes feel a little in the dark. I’d love to see you share your processes with them in more depth.

8. Poor delegation of work from a manager

Hi, I was reviewing my tasks for the upcoming quarter and I noticed that I have been assigned a larger workload than other team members. Though I am grateful for the additional responsibility, I am concerned that I will have too much on my plate. Can we grab a quick one-on-one soon to go over my workload?

9. A manager who expects contact outside of working hours

I’ve seen recently that you have sent a lot of emails and messages outside of our typical working hours. I put a lot of value into my work/life balance so I can come to work and give my fullest. Please understand that while you won’t get an immediate response from me, I will address your messages as soon as I can the next day.

10. Working under a micromanager

Hi, I feel like you are very attentive when it comes to monitoring my output and productivity. I would prefer a little more autonomy over my work. Could we set up a meeting where we can discuss an action plan that supports both of us?

Does constructive feedback have to be positive?

Though it can be good practice to frame constructive feedback in a positive way, it does not have to fundamentally be positive in nature. The goal is to help someone improve, and sometimes to see the change that needs to be made, someone will need a little tough love along the way.

Constructive feedback requires focusing on someone’s behavior and inviting them to make changes. Naturally, people don’t always want to hear a negative perception of themselves, and it can take a lot of mental work to open ourselves up to the idea of change.

Keeping discussions civil and with a focus on positivity needs to be the priority. Delivering thanks is such a small act, but it can have a significant impact. In fact, 69% of employees respond positively to thanks from their managers.

How to deliver constructive feedback

Learning how to deliver constructive feedback is a subtle art form. Luckily, there are several easy steps to keep in mind when trying to deliver feedback. Though not all of these steps may be needed, it is worth bearing them in mind to ensure that the feedback process is productive for all participants.

1. Decide if a feedback is really needed

Firstly, is the feedback actually needed? Sometimes, managers can decide that feedback should be given out based on their own personal biases. For example, employees could simply approach a task in a different manner than the manager might like. If the task is still completed on time and to success, is feedback really necessary here?

Sometimes, a manager might need to consider their own biases before delivering a round of feedback. Just because an employee does something differently doesn’t make it inherently bad. Before you know it, the feedback could be flipped, and it is the manager who has something to learn instead.

2. Do your prep

When delivering constructive feedback to anyone, whether they are senior, junior, or on the same level as you, you need to ensure that you have a game plan in place. Having even a brief plan will help keep discussions on track, ensuring that the feedback is delivered as effectively as possible.

Prepare an outline and structure for the conversation in advance of your meeting. Make sure that the first thing addressed is the issue itself, and possibly how it has come to pass. Before the session, think about possible solutions to the problem. However, you must make sure that you actively work with the person receiving feedback to reach a path and solution that works for them best.

3. Keep the focus on the work, not the person

This is one of the most important parts of delivering feedback since it should be about empowerment and providing professional development. Though the issue might have arisen as a result of some flaw in a person’s character or behavior, such as poor time management, this flaw shouldn’t be the center of constructive feedback.

Instead, the focus should be placed on work and the impact the flaw has upon it. So, someone with poor time management might struggle to meet deadlines and juggle multiple tasks at once. Rather than critique their character, it might be better to focus on their workload. Can anything be delegated to other employees to give them more time? Are there any tools or processes that could help them manage deadlines more effectively? Are there blockers elsewhere that are preventing them from delivering their tasks?

Constructive feedback can really help to undo some of the frustrations that can exist within a team. However, all feedback passed on must be kept focused on the work being done, and not be used as a thin veil to attack an individual through.

4. Find the right time and place

There is always a time and a place when it comes to delivering constructive feedback.

Consider a one-on-one or a session like a performance review. These are the best places to pass along feedback as, by their nature, they encourage discussion.

Another place that can be right, depending on other factors, could be after team meetings. Sometimes, it can be helpful to just have someone hang back for five more minutes while you go over something. On the other hand, it is also easy to see why this isn’t the best place to give feedback. Someone might already be moving on mentally, with their brain focused on their tasks for the rest of the day. It might even feel to them like you are a teacher holding them back after a lesson!

Of all the times and places that you shouldn’t offer feedback, the one you should try to avoid at all costs is the blurt in front of colleagues. Even if what you say mirrors the constructive feedback examples listed above, feedback should be kept private. It is for personal development only. If you wish to evaluate the team as a unit, there is a time and a place for that. Focusing on one member in front of all is only going to create division.

5. Stay professional and polite

No matter if positive or negative feedback is delivered, both parties need to ensure that they stay as professional as possible. At the end of the day, feedback is supposed to help us grow but it isn’t always the most pleasant thing to hear. It requires a lot of self-confidence and willingness to actively listen to what we might perceive as criticism.

Those giving feedback need to ensure that their tone remains friendly, honest, and professional. Those receiving need to ensure that they don’t become defensive and respond with their own feedback – that is not what the session is for.

Employee feedback sessions should always be a two-way dialogue. If it feels like things are breaking down into a lecture, it might be time for a tone check and a regroup.

6. Follow up

No feedback session is complete without tangible steps to follow toward improvement and a proposed timeline for changes to be implemented. Whoever receives the constructive feedback should leave the session feeling like they know the path ahead of them and what it will entail.

Of course, this means that whoever delivered the feedback also needs to be prepared to follow up and ensure that good progress is being made. As soon as possible after the feedback session, the person who delivered the feedback should make a record of what was discussed and the outcomes reached. By then uploading it to the relevant section of the company’s intranet, it can be accessed by both!

How to accept constructive feedback

In our constructive feedback examples listed above, we’ve only talked about delivering meaningful feedback. A big part of the feedback process is learning how to hear constructive feedback and process it yourself.

1. Remember that it is not an attack

It is never easy to hear that we are doing something that might not be quite right. However, it is important to remember that true feedback, like the constructive feedback examples we have listed above, is not meant to be an attack on your character. If someone has decided to give you feedback, it is usually just meant to be an avenue for you to explore together.

2. Actively listen

As part of taking on board what is being said, you need to pay attention to what is actually being said. Active listening is one of those important communication skills that can really set you up for success, and feedback sessions are a great way to practice.

Pay attention to the constructive feedback examples we have listed above, and think about how you would respond if they were said to you. What are the pieces that require the most attention from you? If someone said one of the feedback examples to you, would you be able to actively pull out examples of your own to either corroborate or politely oppose their view? Listen to what they are saying, but don’t get caught up in what you perceive to be the more negative aspects.

3. Have a plan for improvement

A big part of any plan for constructive feedback has to be the follow-up. What are you going to do that will demonstrate that you are taking actionable action to work on what has been outlined in your feedback? Though you and your mentor or manager should have a plan together that you can both access, there is no reason why you cannot have one of your own, too.

Creating a feedback culture in your workplace

The above constructive feedback examples show how easy it is to reframe your words and get to the heart of an issue without being too blunt. Many people want to work in a culture where giving feedback is a regular activity that is delivered without much thought. However, in any workplace where poor communication skills are rampant, this needs to be addressed first.

By regularly providing constructive feedback to employees and encouraging them to do the same in return, employees feel like their opinions matter. Positive feedback is regularly provided, rather than just in an annual performance review, and it means that the entire team is hearing what they do well and where they could stand to make improvements frequently.

Your intranet software could play a massive role in how you manage employee feedback. Even if you have remote employees or frontline workers scattered across the country, the intranet gives you a quick and easy way to share positive feedback with the entire team, no matter where they are located.

Feedback also doesn’t need to be formal. Quizzes, polls, or even just a comment thread can be quick and easy ways of gathering honest feedback and upping employee engagement all at once. Wouldn’t you instead fill in a quiz instead of a boring form?

An intranet is the perfect place to host this! Bring together your workforce while connecting and engaging them in a way that makes sharing positive feedback effortless. Remember, and repeat this with us: Keep👏 feedback👏 focused👏 on👏 the👏 work👏 and👏 not👏 the👏 person!👏

info@axerosolutions.com

info@axerosolutions.com 1-855-AXERO-55

1-855-AXERO-55